From Africa to Wimbledon & Beyond…

Michelle was born in Nyasaland (now Malawi), where her South African father ran the tiny Nyasaland Times, and her Belgian mother wrote a weekly gossip column. But the days of genteel colonial society were numbered, and in 1963 the family moved to England, where she was educated in Wimbledon and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

Michelle was born in Nyasaland (now Malawi), where her South African father ran the tiny Nyasaland Times, and her Belgian mother wrote a weekly gossip column. But the days of genteel colonial society were numbered, and in 1963 the family moved to England, where she was educated in Wimbledon and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

There she read Biochemistry and also made her first serious attempts at writing: two Mills & Boon-type novels, written in a matter of weeks and summarily rejected (‘with good reason!’ she says), followed by a couple of children’s fantasy novels – also rejected, although more encouragingly.

By then she was in the grip of the writing bug. She even managed to ditch the usual final-year laboratory project in favour of a written thesis: simply because, as she admits, ‘I’d stumbled on a great story: Soviet genetics driven underground by an illiterate crony of Stalin’s. How could I resist?’

That got her a First, but by then she’d decided against a career in science. ‘I knew I wanted to write, but I didn’t think I’d be able to make a living at it, so I looked around for a day job: something that would pay the bills while giving me time to write. Like an idiot, I chose the Law. It was a spur-of-the-moment decision. One rainy afternoon I was leafing through a careers brochure when I came across an article on being a solicitor. I thought, ‘that’ll give me a few years’ breathing space before it gets too demanding, so why not?’’

Of course it didn’t turn out quite like that.

Of course it didn’t turn out quite like that.

Michelle qualified as a solicitor with a big City firm, and was soon up to her neck in big-ticket scientific litigation. Multinational drug companies slugging it out over who owned which gene; tobacco companies battling to defend themselves against plaintiffs dying of cancer. ‘There were times,’ she says, ‘when I didn’t exactly feel on the side of the angels.’

Outwardly she was a success, having been made a partner five years after qualification. But the strain of all-night meetings and missed weekends was beginning to tell. Then in 1996 her father died, and that proved a wake-up call.

‘I realized that I wasn’t doing what I really wanted to do, and although I was earning lots of money, I’d never have time to spend it. So I decided to negotiate a year off, to get myself sorted out. At the time, that was unheard-of in a City firm. They didn’t even have a sabbatical policy. But I told myself that if they said no, I’d quit anyway, and that at least gave me the courage to ask. To my astonishment, they said yes.’

Michelle spent 1997 travelling around Peru, Ecuador, South Africa, France, and the States, and finishing the first draft of Without Charity…

‘It’s no coincidence that the story is all about seizing the moment. And it’s also personal in another way, as it’s partly set during the Boer War, which bankrupted my father’s family. Although they were fiercely loyal to the Crown, they fell victim to the scorched earth policy when the British burnt most of their farms – by mistake!

‘It’s no coincidence that the story is all about seizing the moment. And it’s also personal in another way, as it’s partly set during the Boer War, which bankrupted my father’s family. Although they were fiercely loyal to the Crown, they fell victim to the scorched earth policy when the British burnt most of their farms – by mistake!

To my surprise, researching the book in South Africa turned out to be a pretty emotional experience. I kept wishing my father could have been with me. For example, when I visited the little farming town of Reitz, where the early Pavers settled in the nineteenth century, I found a portrait of my great-grandfather, the second mayor, hanging in the Town Hall, and even a ‘Paver Straat’.’

After her year off Michelle returned to the City, and realized on the very first day that it was a mistake…

‘There were three thousand e-mails clogging up my computer, and all I could think about was Without Charity. So I sent the manuscript off to a publisher, and then, without waiting for a reply, I resigned. A couple of months later, I was offered a publishing contract – to my relief!’

Without Charity was selected by WH Smith (Britain’s biggest booksellers) as one of a handful of debut novels to be awarded their Fresh Talent accolade. Since then, Michelle has worked as a writer full-time.

Michelle’s second book, A Place In The Hills, tells two intertwined love stories that take place two thousand years apart…

‘I’ve always been passionate about ancient Rome, and I’ve always loved the idea of a contemporary character having a real connection with someone in the distant past. But why a love story? Well, in a way, I was trying to prove to myself that great love – true, self-sacrificing, altruistic love – can actually exist. To my surprise, I ended up convincing myself. Although what the reader will think about that is up to them.’

A Place In The Hills was short listed for the 2002 Parker Pen Romantic Novel of the Year award. Her third book, The Shadow Catcher, was the first in the EDEN trilogy.

A Place In The Hills was short listed for the 2002 Parker Pen Romantic Novel of the Year award. Her third book, The Shadow Catcher, was the first in the EDEN trilogy.

‘It’s set in colonial Jamaica,’ she says, ‘at a crucial period of transition: the slaves had been freed, the great sugar plantations were in decay, and there was an incredible sense of uncertainty. The tone of the story is what I’d call Caribbean Gothic. With my background I’m obviously drawn to themes of the Empire under threat, but the EDEN trilogy is as much about class, and the position of women in Victorian society.’

‘Researching it was an experience in itself. In Jamaica, everyone seems to know everyone else, so if you’ve got family there, as I have (this time on my mother’s side), you’re instantly connected to what seems like half the population. For example, my cousin has a farm on the north coast, and his wife’s friend’s mother is a leading light in the Jamaica Historical Society, and she’s married to the grandson of a Victorian vicar who just happened to write the seminal work on Jamaican magic back in the 1890s, and so it goes on…’

In 2003, Michelle started work on an idea for a series of six books that had been brewing ever since childhood. Set in prehistoric, hunter/gatherer times, in a world of dark enchantment, menace and superstition, the stories revolve around a boy – and his wolf companion – growing up, fighting for survival and unleashing a powerful magic…

‘Chronicles Of Ancient Darkness is my way of achieving what I used to dream about when I was ten years old: to run with the wild wolves in the prehistoric Forest.

‘As a child, my passions were myths, animals, and how people actually lived in the distant past. I read and re-read Roger Lancelyn Green’s tales of the Norsemen and the Ancient Egyptians. I pored over pictures of Stone-Age hunters scraping hides and knapping flints. I bought a copy of Culpeper’s Herbal, and dug up my parents’ lawn to grow outlandish medicinal plants. And I read everything I could find on animal behaviour: especially about wolves. (Wolf researchers such as David Mech, Michael Fox and Lois Crisler quickly became my heroes.)’

‘As I grew older, I managed to do a fair bit of travelling in out-of-the-way places: Iceland, Norway, South America, the Rockies; often hiking on my own so as not to dilute the experience. I worked as a volunteer on a wildlife survey in the Carpathian Mountains, where I heard red deer bellowing in rut, and found fresh wolf-tracks calmly crossing my own, and nearly lost my nerve when I came across an enormous pile of steaming dung. (Bear? Bison? I didn’t hang around to find out.)’

‘As I grew older, I managed to do a fair bit of travelling in out-of-the-way places: Iceland, Norway, South America, the Rockies; often hiking on my own so as not to dilute the experience. I worked as a volunteer on a wildlife survey in the Carpathian Mountains, where I heard red deer bellowing in rut, and found fresh wolf-tracks calmly crossing my own, and nearly lost my nerve when I came across an enormous pile of steaming dung. (Bear? Bison? I didn’t hang around to find out.)’

‘Gradually I realised that the old enthusiasms hadn’t gone away; they’d just broadened and taken root. And when I had the idea for Chronicles Of Ancient Darkness, it all came together…’

‘In fact, though, I’d had the basic idea back at University, in the early 80s. I’d even written it: a story about an orphaned boy struggling to survive with his beloved wolf-cub. But I’d set the story in the ninth century, and the historical context kept getting in the way. So I put the manuscript in a box-file and shoved it to the back of a cupboard. For twenty years the idea of the boy and the wolf simmered away in my subconscious. It nagged me. I really wanted to write it. But I knew I hadn’t found the right context. Then, I unearthed the box-file and took another look at my twenty-year-old notes. The answer just leapt out at me. This isn’t a story about history. It’s about prehistory. As soon as I realised that, everything fell into place.’

‘I’d always read quite a bit of anthropology: The Golden Bough, The White Goddess, Boyer’s Religion Explained. And also archaeology: David Lewis-Williams on prehistoric cave art; Grahame Clark on Mesolithic hunter-gatherers; Steven Mithen’s Prehistory of the Mind and After the Ice Age. But now it had a focus: Torak’s world.’

‘To learn what the Clans of Torak’s world use for weapons, clothes, food and shelter, I studied the Mesolithic peoples of Northern Scandinavia, including the Maglemosians, and the Ertebølle and Kongemose cultures. I also borrowed from the more recent past: from the survival strategies of traditional Inuit and Native American peoples, and many others.’

‘Similarly, in trying to understand how my hunter-gatherers actually think, I’ve been guided by anthropology: not only that of the Inuit and the Native American peoples, but also the Ainu of Japan and the Sami of Lappland; the San and the Eboe of Africa, and the Aborigines of Australia.’

‘And yet – despite all of this, Torak’s story would probably still be just a pipe-dream, if I hadn’t met the bear.’

‘And yet – despite all of this, Torak’s story would probably still be just a pipe-dream, if I hadn’t met the bear.’

‘It was a few years ago, in the Sierra Nevada of southern California, and I was hiking alone on a deserted mountain trail. Suddenly, on the opposite side of the stream I was following, a large female black bear and her two cubs appeared out of nowhere. One moment I was in the twentieth century; the next, I was back in the prehistoric forest.’

‘An old rancher in Wyoming had warned me that a female bear with cubs is at her most dangerous. He’d also told me that as bears can’t see too well, and hate surprises, it’s vital to make a noise to let them know you’re there: his tip was to sing! The mother bear and her cubs was only thirty feet away from me, on the other side of the stream – but she clearly hadn’t spotted me yet; and my way home led right past her. I couldn’t hope to creep by unnoticed; I had to tell her I was there. So I took a deep breath and launched into Danny Boy.’

‘To my horror, instead of just watching me go, she pricked up her ears and started purposefully across the stream – towards me. That’s when the fear really kicked in. If I made a wrong move, she might attack. And I had no defences. All I could do was try to persuade her that I wasn’t a threat. I stopped. She stopped in mid-stream. We looked at each other. She rocked slowly from side to side, as if considering whether to rear up on her hind legs and go for me. For what seemed like a lifetime I side-stepped slowly past her. She watched me all the way. Then, finally, my path dipped out of sight – and I ran like hell.’

It was the most terrifying and exhilarating experience of my life. It also felt weirdly as if I’d been back in time. In those brief moments when I was facing the bear, thousands of years of civilisation were suddenly irrelevant; I knew what it was to be prey. I’d been in Torak’s world.’

CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS has now been sold into every major publishing market worldwide, setting records in many of them.

So what will Michelle write after CHRONICLES?

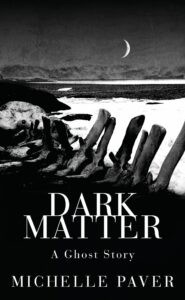

‘I didn’t plan it”, she says, ‘but I ended up writing a ghost story.’

Here’s how it came about.

‘A few years ago, while I was deep in Torak’s story, I’d taken a holiday to the High Arctic, travelling by ship around the Spitsbergen archipelago (or Svalbard, to give it its official name). It was summer, so there was this endless, rather eerie light, and the whole place was teeming with wildlife: seabirds, Arctic foxes, reindeer, seals, walrus, polar bears.’

‘A few years ago, while I was deep in Torak’s story, I’d taken a holiday to the High Arctic, travelling by ship around the Spitsbergen archipelago (or Svalbard, to give it its official name). It was summer, so there was this endless, rather eerie light, and the whole place was teeming with wildlife: seabirds, Arctic foxes, reindeer, seals, walrus, polar bears.’

‘That was overwhelming in itself, but we also put in at several abandoned mines and derelict trappers’ camps. I remember standing at the edge of one of these, looking out over this desolate, windswept bay, trying to imagine what it would be like to be here on your own. I think what most impressed me most was the peculiar, unnerving stillness of the place, which one could sense even behind the noise of the wind and the seabirds. It was as if the land was watching all these tiny living creatures busily going about their lives.’

‘I knew that at some stage, I would write a story set in Spitsbergen, but I didn’t know what it would be about, because at the time I was deep into writing CHRONICLES. So I just took loads of notes, and put Spitsbergen to the back of mind. It was while I was writing GHOST HUNTER that I began thinking seriously about writing a ghost story. It was winter, there wasn’t any snow in Wimbledon, and I was missing the Arctic. This was when I realized that the Arctic would be my setting: DARK MATTER would be a polar ghost story. It was incredibly exciting, because I immediately realized the significance of the polar night. I saw my protagonist overwintering alone in his haunted camp. How would he cope in the polar night, which lasts for months?’